Multiculturalism is the main reason why I return to Toronto as often as possible, a half-dozen times in the past decade. I love the diverse population—chatting to an Eritrean taxi driver about the struggles in her country, dining on sublime dim sum with a Hong Kong-born chef whose har gow (shrimp dumplings) arrives orange thanks to a mix of butternut squash (more on the restaurant Luckee later this week), to shopping for vintage clothing in Little India. So it came as no surprise to me that the Aga Khan Museum, the first North American museum devoted exclusively to Islamic Art, made its debut in mid-September in the northeastern part of Toronto.

Multiculturalism is the main reason why I return to Toronto as often as possible, a half-dozen times in the past decade. I love the diverse population—chatting to an Eritrean taxi driver about the struggles in her country, dining on sublime dim sum with a Hong Kong-born chef whose har gow (shrimp dumplings) arrives orange thanks to a mix of butternut squash (more on the restaurant Luckee later this week), to shopping for vintage clothing in Little India. So it came as no surprise to me that the Aga Khan Museum, the first North American museum devoted exclusively to Islamic Art, made its debut in mid-September in the northeastern part of Toronto.

Aga Khan, the imam and prince of the Ismaili branch of Shia Muslims, who number some 15 million across 25 nations, spent more than $300 million to fund the museum. His renowned collection of art, over 1,000 pieces that span a millennium, has been on view at the Louvre in Paris and Hermitage in St. Petersburg, but now he has a permanent home worthy of the works. It took 18 years from conception to completion, but the debut of the Aga Khan Museum couldn’t have come a better time. With media constantly bombarding us with all the atrocities happening in the Muslim world, it’s downright therapeutic to walk into an exquisite setting bathed in natural light and be dazzled at the beauty of these objects.

The collection is housed in a building created by the Pritzker Prize winning octogenarian, Fumihiko Maki. Artifacts are displayed on two floors, in high-ceilinged white rooms with teak floors. The galleries are centered around an open-air courtyard, which is open to the public free of charge if they simply want to relax and enjoy a cup of coffee and Turkish sweets. Before viewing the works, walk up the lapis-stone stairway into the auditorium, an explosion of teak wood already starting to garner attention for its excellent acoustics.

New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art might have a larger collection of Islamic Art, now housed in its new wing, but the Aga Khan has a good eye for objects. The museum is designed chronologically and starts with a blue Koran from 9th century Iran, calligraphy written in gold. The geometric patterns, whether circles found on the 12th-century robe of a Mongol warrior or a 9-pointed star seen in the woodwork of a 14th-centurty Spanish squinch, are mind-boggling. A rare piece of Iznik ceramics from the Ottoman Empire shows how the color red suddenly appeared in the predominantly “blue and white” patterns of the day. My favorite part of the collection was the brilliantly illustrated pages of the Persian epic, Shah-Nameh, a colorful portrayal on each page, which will be turned every three months in order not to damage the manuscript. An easy 20-minute taxi ride from downtown, the Aga Khan Museum is a great addition to the

Art Gallery of Ontario, the

Ryerson Image Centre, and the other noteworthy art found in Toronto.

Multiculturalism is the main reason why I return to Toronto as often as possible, a half-dozen times in the past decade. I love the diverse population—chatting to an Eritrean taxi driver about the struggles in her country, dining on sublime dim sum with a Hong Kong-born chef whose har gow (shrimp dumplings) arrives orange thanks to a mix of butternut squash (more on the restaurant Luckee later this week), to shopping for vintage clothing in Little India. So it came as no surprise to me that the Aga Khan Museum, the first North American museum devoted exclusively to Islamic Art, made its debut in mid-September in the northeastern part of Toronto.

For a city of only 140,000, Lausanne is blessed with 22 museums. Actually 23 museums if you count the archaeologist I met yesterday who opened a one-room museum devoted to the history of shoes, including her recreation of a Neolithic shoe. Home to the International Olympic Committee or IOC, Lausanne’s best known museum is the

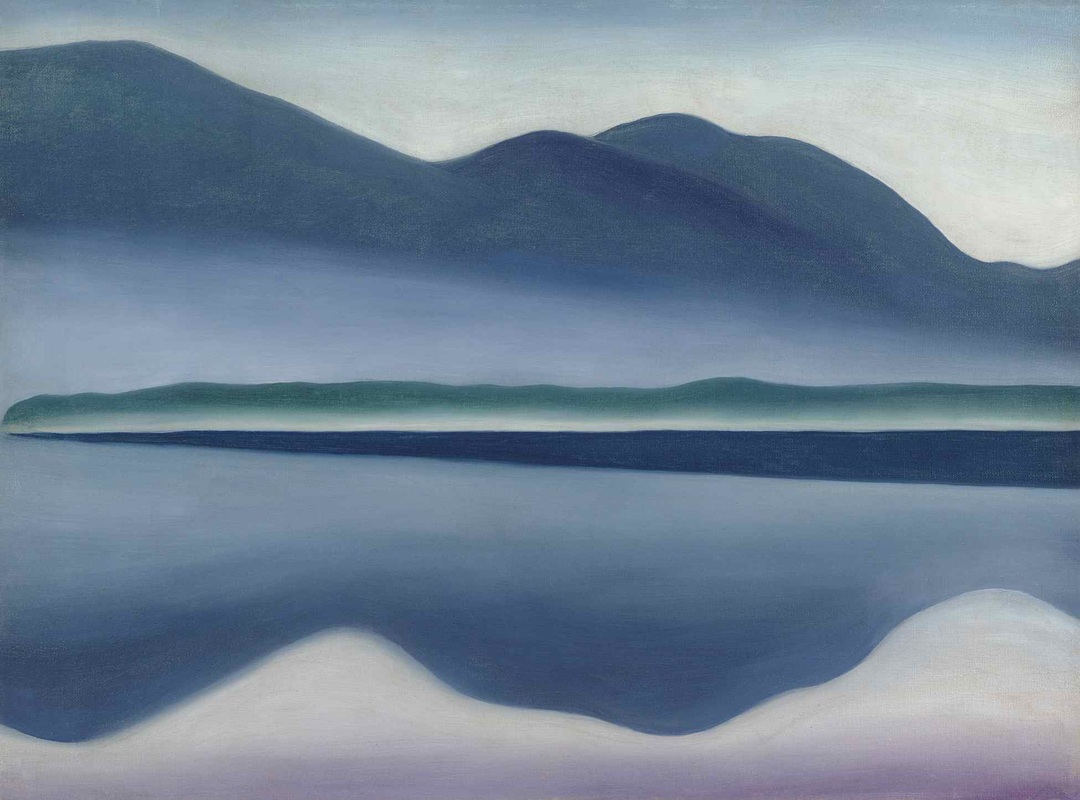

For a city of only 140,000, Lausanne is blessed with 22 museums. Actually 23 museums if you count the archaeologist I met yesterday who opened a one-room museum devoted to the history of shoes, including her recreation of a Neolithic shoe. Home to the International Olympic Committee or IOC, Lausanne’s best known museum is the  In the mid-90s, I was hired by Art & Antiques Magazine to write a story on the period of time painter Georgia O’Keeffe and her husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, lived on the shores of Lake George. This was to coincide with a photography exhibition of Stieglitz’s work at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. I knew renowned abstract sculptor David Smith lived in Bolton Landing, but I honestly had no idea O’Keeffe lived in Lake George, since she’s far better known for her New Mexican motif. From 1918 to 1934, O’Keeffe would spend a good portion of her summer at the lake. She would return to Lake George for the last time in 1946 to spread Stieglitz’s ashes at the foot of a pine tree on the shores of the lake. Today, those ashes lie on the grounds of the Tahoe Motel. Next door, the house they lived in, Oaklawn, is still standing at The Quarters of the Four Seasons Inn. On a wall next to my desk, I have a poster of a dreamy mountain and lake landscape simply titled Lake George (1922). My brother, Jim, purchased this for me at the San Francisco Museum of Art, where the original O’Keeffe oil still hangs.

In the mid-90s, I was hired by Art & Antiques Magazine to write a story on the period of time painter Georgia O’Keeffe and her husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, lived on the shores of Lake George. This was to coincide with a photography exhibition of Stieglitz’s work at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. I knew renowned abstract sculptor David Smith lived in Bolton Landing, but I honestly had no idea O’Keeffe lived in Lake George, since she’s far better known for her New Mexican motif. From 1918 to 1934, O’Keeffe would spend a good portion of her summer at the lake. She would return to Lake George for the last time in 1946 to spread Stieglitz’s ashes at the foot of a pine tree on the shores of the lake. Today, those ashes lie on the grounds of the Tahoe Motel. Next door, the house they lived in, Oaklawn, is still standing at The Quarters of the Four Seasons Inn. On a wall next to my desk, I have a poster of a dreamy mountain and lake landscape simply titled Lake George (1922). My brother, Jim, purchased this for me at the San Francisco Museum of Art, where the original O’Keeffe oil still hangs.  It’s not everyday that I turn around to peer at a piece of art hanging from the walls of a hotel. Usually it’s some commercial print of ocean and seabirds. But last week, while spending the night at the

It’s not everyday that I turn around to peer at a piece of art hanging from the walls of a hotel. Usually it’s some commercial print of ocean and seabirds. But last week, while spending the night at the  To commemorate the 150th anniversary of the publication of Henry David Thoreau’s “The Maine Woods,” the

To commemorate the 150th anniversary of the publication of Henry David Thoreau’s “The Maine Woods,” the  They say Eureka has more artists per capita than any other place in California. A walk around town Sunday introduced me to many of the impressive local wares. My first stop was the

They say Eureka has more artists per capita than any other place in California. A walk around town Sunday introduced me to many of the impressive local wares. My first stop was the  Long before people headed to Niagara on the Lake to sample the world-class chardonnays and rieslings, and prior to outfitters like Butterfield & Robinson arriving on the scene to design exceptional day rides, there was the renowned

Long before people headed to Niagara on the Lake to sample the world-class chardonnays and rieslings, and prior to outfitters like Butterfield & Robinson arriving on the scene to design exceptional day rides, there was the renowned